We were in, what seemed like, the middle of nowhere when my parents drove into the parking lot of the Lexington Antique Outlet. They loved antiquing and I enjoyed taking a jaunt back in time with every stop.

Smells, memories, and laughs flourished while rummaging through things that every household used to have. These trips always brought up stories of the past and would undoubtedly create more to be shared in the future.

As we were strolling through the Lexington store, a book rack caught my attention. Reader’s Digests. We used to get these all the time. I began traversing through some of them and came across one from February 1941. It was the oldest magazine on the rack. Still encased in its original clear plastic, I flipped to the front cover and found the “Articles of Lasting Interest”, now as the Table of Contents. As I glanced down the list, a title popped out at me. It read, “What Makes the Worker Like to Work?” by Stuart Chase. I was fascinated to find out if the answer would still apply today. I bought that Reader’s Digest for $2.

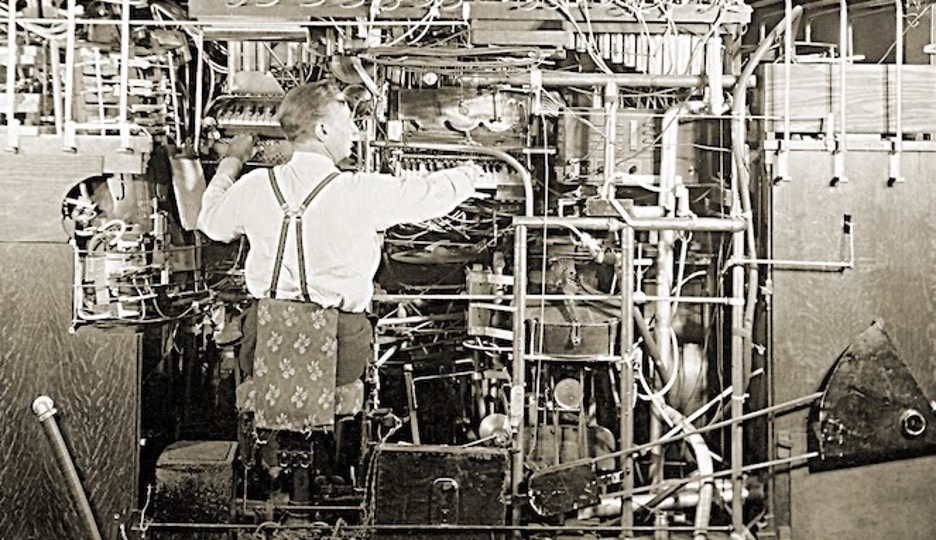

Later that night, I opened it and began reading. The article began with a description of a factory study on production and efficiency in the workplace, which began in 1924 and had been going on for sixteen years. The study was designed and orchestrated by the Western Electric Company’s Hawthorne plant near Chicago. It was, at that time, termed “the most exciting and important study of factory workers ever” and produced what became known as the Hawthorne Effect.

The Hawthorne Effect, in essence, is the premise that workers work harder when they are being observed by supervisors.

Though there are many discrepancies in the way the study was run and in some of the first findings, what was surmised from the exercise was that certain elements of the workplace did lead to higher production and happier workers, and observation by supervisors was part of the discussion. But it’s not really what led to the happiest, most productive employees.

The last sentence of the first paragraph of the article read:

“If managers of other factories, large and small the country over, were aware of things which this huge experiment in industrial relations has found out, American industry could be made over.”

As I continued through the article, and after great details of the study were outlined, the findings were revealed. From this research came these ideals:

Attitude Matters

The attitude of the worker was the largest indicator of increased production in the workplace. Happier employees, even when it meant working on an assembly line or constructing what was then known as relays, were a high indicator of factory overall success.

Freedom Fosters Taking Responsibility

A sense of freedom brought about a sense of responsibility. In this case, it referred to workers being permitted to move around the plant freely and to speak to each other without being shushed or reprimanded. With this freedom, researchers found that employees began to take responsibility for their actions and to discipline themselves, and work better as a team.

Feelings Mattered Most

Feelings counted more than hours of labor and more than wage levels. Researchers discovered that even with all the adjustments made throughout the study—changing lighting brightness, changing hours, more breaks vs. fewer breaks, rates of pay increases—the most important indicator of production was the individual feelings of the workers. Not that all these adjustments had no effect, but they were not the MOST important indicators of workers’ success.

Listening Does Have a Place in Leadership

When felt listened to by superiors, employees had more pride in the company. Employees had valuable comments, and when they felt heard by the boss, they carried the company in higher esteem and therefore were “with the company” as opposed to “against the company.” Even when employee suggestions were not always adhered to, they still valued being listened to.

As supervisors continued to learn from this research, they began to think of the employees more as people versus simply units of labor. Factory workers became better teams and were happier as a result.

Further descriptions of findings suggested the following. Employees were motivated by certain characteristics present in the workplace.

Finding A Place to Take Root

Every worker has an inner urge to find an environment where they can take root and settle in. They want to find their place. It’s not the same as finding a home, but it is similar in that it brings stability, which in turn brings comfort.

Having A Function

It becomes more than just a title or a salary. It’s the function of work. The employee has a skill that is useful and needed.

Having A Purpose

Once employees understand their function, their motivation goes a step further. When they know and understand their purpose, they are driven to work harder and are happier doing the work.

Feeling Important

Feeling important is not to be confused with a feeling of importance. The first is where the employee wants to feel like an important contributor and the latter meaning he wants to be more important than others within the factory or company. When employees felt their contribution was valued and important, they were more motivated to continue the work.

What can be learned from an article from Reader’s Digest back in 1941? If this research and these findings were just coming to light back then, where are we today? What does the workplace look like today? Eighty years later, have we mastered the workplace, and have we mastered the art of supervising and leading?

Look around the country and ask yourself, what is the attitude in the workplace? Do workers only work hard when the boss is watching? Or do the other factors mentioned above come into play?

As leaders, what freedoms do we choose to allow or reject? Are the feelings of our employees and colleagues respected and taken into consideration? Do we give our team a voice to be heard and are we listening? Is our organization a place where people can take root and thrive? Do our employees and teams know and understand their function and their purpose? Do they feel important enough to have pride in and fight for the organization, including suggesting ways to improve?

If the factories of 1941, right after the insurmountable and devastating Great Depression, learned how to produce efficient and productive teams in times of great need, we should see these lessons reaping great rewards in today’s world. Do we?

The truth is, we do see great teams working together for success, but there are also many that fall short. What a great reminder to look in the mirror of our organizations, large and small alike, to delve into the hearts and minds of the employees and team members who we count on for efficient and productive outcomes.

Where is your company in teamwork? Is your company thriving? Is your organization leading the way in team and leadership development?

Before your organization can make a difference in the community, state, nation, or world, you must first make a difference in the lives of the people that make up the teams you lead.

We can learn from history, and it is fun to see what was written before us by leaders nearly a century ago. Hopefully, lessons from the past can help guide us to a brighter future.

Sources:

- Reader’s Digest, 1941

- Hawthorne Effect – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hawthorne_effect

- Hawthorne Works – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hawthorne_Works

- Elton Mayo – https://www.bl.uk/people/elton-mayo